For generations, the world’s best-known adventurers have been men—Marco Polo, James Cook, Ferdinand Magellan, Ernest Shackleton and Edmund Hillary. Their journeys were recorded, celebrated and taught as proof of human ambition and endurance. Many traveled with official backing, funding and protection, sent out with the support of powerful governments and institutions.

But history holds another story, too: women who explored with far less permission and far more risk. They traveled despite the rules, the restrictions and the assumptions about where women “belonged.” Some disguised themselves, some traveled alone and many pushed past real danger to follow curiosity across oceans, deserts and mountain ranges.

At Natural Habitat Adventures, that kind of spirit matters. Our Women’s Journeys are built around the idea that travel can be both bold and deeply supportive—an experience shaped by connection, shared discovery and the freedom to go farther than you thought you could. The women below did exactly that in their own eras, carving out space in the world through grit, intellect and relentless wonder. If you’ve ever felt pulled toward a destination that scares you a little—in the best way—let them be your invitation.

1. Jeanne Baret

Allegorical portrait of Jeanne Baret dressed as a sailor, dating from 1817, after her death. © Public Domain

In February 1767, Baret, an expert botanist, disguised herself as a boy called Jean to join the naturalist Philibert Commerson on the ship Étoile. Cpmmerson had been chosen as “Doctor-Botanist and Naturalist to the King” on French explorer Louis Antoine de Bougainville’s round-the-world expedition. At that time, the French navy did not allow women on ships at all. This was a time when most European peasants didn’t ever see more than a day’s travel from where they lived. But Jeanne Baret became the first woman to circumnavigate the globe.

With Commerson riddled with bad health on the trip, it was Baret who collected thousands of plant specimens on her own during the more-than-year-long undertaking. One plant believed to have been discovered by her was the bougainvillea, named after the leader of the expedition.

While her gender was discovered when the party reached Tahiti, instead of being punished, she was honored as an exceptional botanist and explorer and even received a stipend from the king for her work. But were it not for a small mention in Bougainville’s book, A Voyage Round the World, Baret’s amazing achievement would never be known today.

2. Alexandra David-Néel

Alexandra David-Néel in Tibet, 1933 © Wikimedia Commons

In 1911, French former opera singer Alexandra David-Néel told her husband she would be back in a year and a half. Then, she set out on what would become a 14-year expedition through Asia to the forbidden city of Lhasa, determined to “show what the will of a woman can do.”

Alexandra explored the Himalayas in the frigid winter, sleeping in the snow, and even had to gnaw on the leather from her boots to stave off hunger. She pretended to be a beggar to sneak into the Tibetan capital in 1924, aged 55, which at the time had been sealed off from the outside world. Eventually, she wrote about that ruse in My Journey to Lhasa, expressing her joy at being “en route for the mystery of these unexplored heights, alone in the great silence, tasting the sweets of solitude and tranquility.”

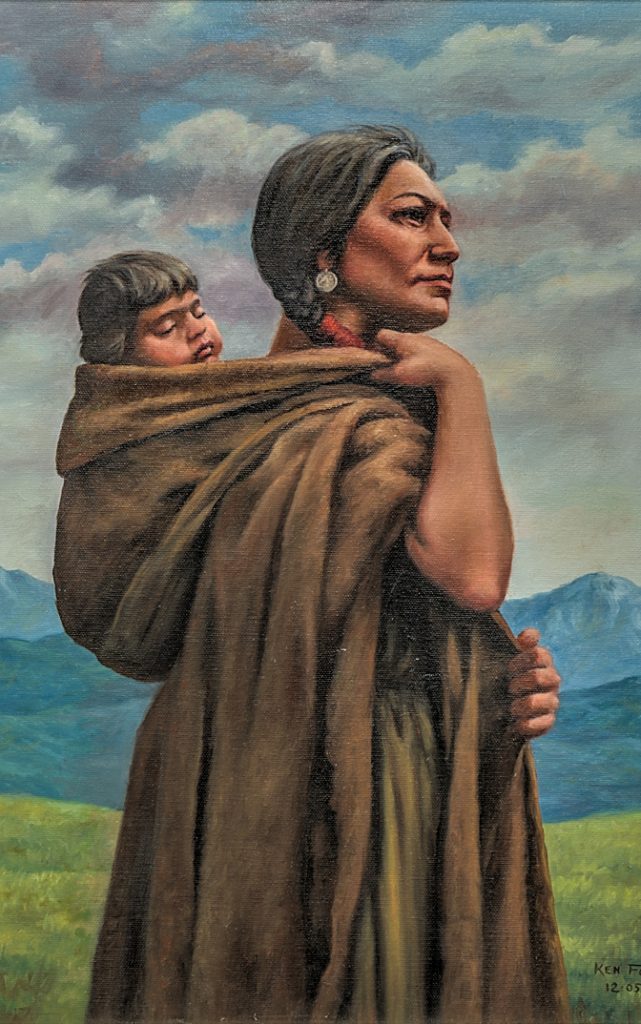

3. Sacagawea

Portrait of Sacagawea at the National Mississippi River Museum & Aquarium. © Public Domain

Lewis and Clark became famous for their early-19th-century expedition into the previously uncharted lands of the American West, but their two-year mission would have been impossible without their guide and translator, Sacagawea, a member of the Lemhi band of the Native American Shoshone tribe.

The life of Sacagawea was short but intensely eventful. She was captured by the rival Hidatsa tribe when she was 12, before she later married French-Canadian fur trader Toussaint Charbonneau. Her language skills allowed Lewis and Clark to communicate with tribes and make vital supply purchases, and she had a calming effect on the skeptical Native Americans they encountered.

Sacagawea’s intimate knowledge of the difficult terrain also proved invaluable as she successfully guided Clark’s group through the Rocky Mountains using a route known today as Bozeman Pass. “The Indian woman…has been of great service to me as a pilot through this country,” Clark wrote in his journal.

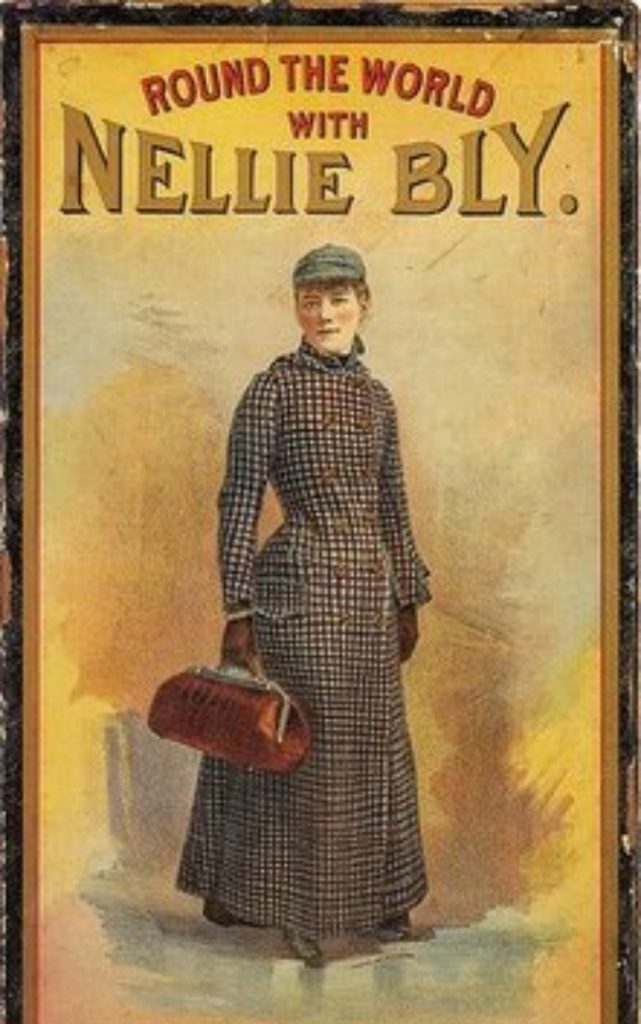

4. Nellie Bly

Cover of the 1890 board game Round the World with Nellie Bly. © Public Domain

Nellie Bly started her claim to fame in 1864 when she feigned mental illness to gain admission into Blackwell’s Island Insane Asylum, one of New York’s most notorious mental hospitals. She then wrote a newspaper exposé that changed the course of American journalism. Basically, she pioneered an entirely new, immersive style of reporting now known as investigative journalism.

A few years later, Bly made waves again with a pitch she made (and had to fight for) to the newspaper “New York World,” which originally thought they should send a man in her place. She took the novel Around the World in Eighty Days by Jules Verne as a challenge and completed a trip around the world in 72 days, 6 hours, 11 minutes, and 14 seconds—mostly alone—and still somehow had time to meet up with Verne himself when she passed through France.

To cover her 24,899-mile trip, she traveled by everything from steamships and donkeys to trains and rickshaws and horseback. She sailed against a monsoon in the South China Sea and recounted mesmerizing sights from alligator hunters in Egypt to snake charmers in Sri Lanka.

5. Harriet Chalmers Adams

American explorer Harriet Chalmers Adams (1875-1937) © Library of Congress, Public Domain

Harriet Chalmers Adams, born in 1875, started some bold adventures at the age of eight when she traveled through the vast Sierra Nevada mountain range on horseback with her dad. A bit later in 1903, she went on a journey with her husband, Franklin Pierce Adams, that took them 40,000 miles through Central and South America, climbing peaks in the Andes at 23,000 feet, descending into the Amazon, and traversing an ancient Inca highway.

Adams documented her exploits for National Geographic. “There is no reason why a woman cannot go wherever a man goes—and further,” she proclaimed in 1920. After being denied acceptance into the New York-based Explorers Club, she became the founding president of the Society of Women Geographers in 1925.

6. Ida Pfeiffer

Ida Pfeiffer, photographed by Franz Hanfstaengl. © Public Domain

In the mid-1800s, Ida Pfeiffer trekked to Istanbul, Jerusalem and Giza and on her return trip, she detoured through Italy, because why not? Between 1846 and 1855, the Austrian adventurer journeyed an estimated 20,000 miles by land and 150,000 miles by sea through Southeast Asia, the Americas, the Middle East and Africa—including two trips around the world.

She often made these trips alone, and she loved to collect plants, insects, molluscs, marine life and mineral specimens on her way. Her journals went on to be translated into seven languages —but even after all of her undeniable success, Pfeiffer was barred from the Royal Geographical Society of London simply because she was a woman.

7. Isabella Bird

© Public Domain

Because of her chronic illness, insomnia and even a spinal operation for a tumor when she was 20 years old, doctors recommended leisurely travel and rest. Well, the British Bird took that advice and amped it up a bit. She boarded a Cunard Royal Mail steamer in 1854 for her first transatlantic crossing to Canada and the United States.

Loving travel, she would go on to become a full-fledged explorer, writer, photographer and naturalist who would climb volcanic peaks in Hawaii, face off with a grizzly bear near Lake Tahoe, live with the Indigenous Ainu tribe in Japan, camp deep in the Himalayas and caravan through little-known parts of Iran, India, Australia, Malaysia, China, Kurdistan and Turkey. Her last trip was to Morocco when she was 72. She wrote about her extensive travels in 10 books and became the first woman fellow of the Royal Geographical Society in 1891.

8. Annie Smith Peck

1911 Hassan Cigatette Trading card of Annie Smith Peck. © Public Domain

Annie Smith Peck was one of the greatest mountaineers of the 19th century, but her focus in her lifetime was sadly never on her accomplishments, but on the outrage that was sparked because of her climbing attire of a long tunic and trousers. She responded defiantly: “For a woman in difficult mountaineering to waste her strength and endanger her life with a skirt is foolish in the extreme.”

She was also a passionate suffragist who, in 1909, planted a flag that read “Votes for Women!” on the summit of Mount Coropuna in Peru. The north peak of Huascarán in Peru was even renamed Cumbre Aña Peck in 1928 in honor of her being its first trailblazing climber. Peck climbed her last mountain—the 5,367 ft Mount Madison in New Hampshire—at the age of 82.

9. Mary Kingsley

Portrait of Mary Kingsley (1862-1900).

Kingsley was a Victorian lady, a time when proper, respectable women didn’t dare walk the streets of London unaccompanied. When her parents died, she took her inheritance and, at 30, set out alone to explore uncharted parts of West Africa. She canoed up the Ogooué River and pioneered a route to the summit of Mount Cameroon, never before attempted by a European.

In other firsts, she was also the first European to enter remote parts of Gabon, where she made extensive collections of freshwater fish on behalf of the British Museum. She had close encounters with gorillas, leopards, hippos and crocodiles, and went on to write a controversial book, Travels in West Africa, in which she articulated her fierce passion for protecting the rights of Indigenous people. The moleskin hat she wore throughout her travels is even on display at the Royal Geographical Society.

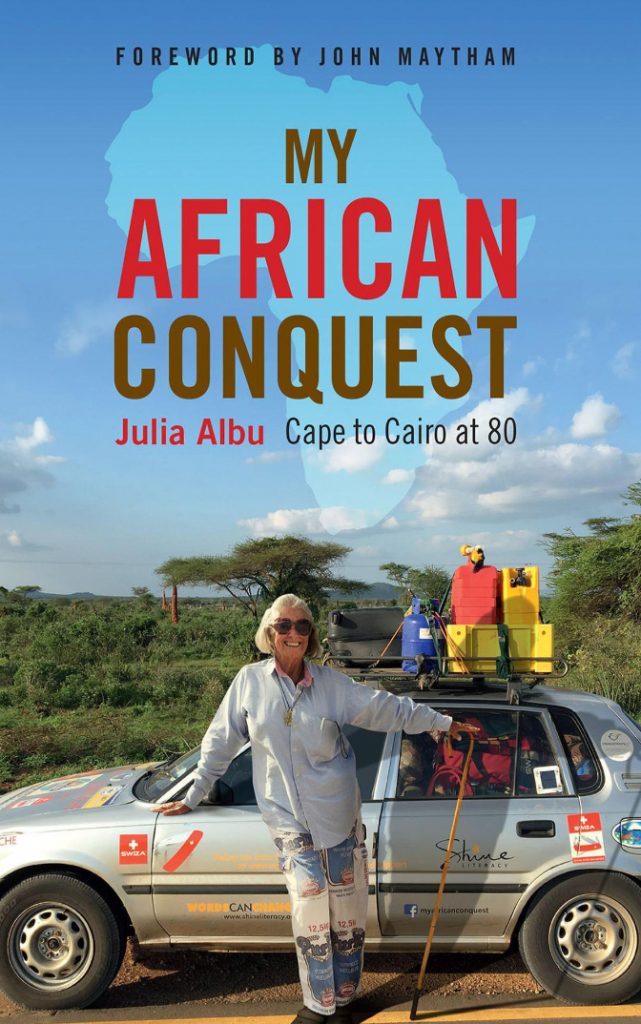

10. Julia Albu

Cover of Julia Albu’s book, My African Conquest.

Last but definitely not least is the modern-day 80-year-old Julia Albu from South Africa, who drove herself from Cape Town to Cairo in a battered Toyota Conquest on a solo five-month journey. She crossed notoriously difficult borders and military blockades by saying she was going to London to have tea with the Queen.

Julia Albu never set out to be an adventurer, but one morning, as she was listening to the radio, she became furious when the chat turned to then-President Jacob Zuma and his extravagant taste in cars. Albu says, “I phoned in immediately to say I was going to be 80, and my car, Tracy, was a 20-year-old Toyota, and she ran beautifully. We could happily drive to London together, so why Zuma needed all these new cars was beyond me.”

Albu pledged on air to drive to Buckingham Palace to have tea with the Queen—and what had begun as a joke actually happened when her partner died and she thought ‘My goodness, there really isn’t much of life left—I feel like I’m 36 from the shoulders up and 146 from the shoulders down, and I wanted the younger me to win for once.”

And win it did. She describes skinny dipping at midnight in Tanzania and camping with 20-somethings in the Danakil Depression in Ethiopia, a place often called the “gateway to hell.”

“I think I got my moment of purest joy when I was driving alone through the Sudanese desert on the long road to Khartoum,” she said. “My tape of hymns was playing at full blast, and I was singing ‘Jerusalem’, thinking about England’s green and pleasant land while a shepherd shuffled through the sand in the distance.”

Albu’s epic trip ended in Egypt, where she was ultimately held at border control.

As Albu eloquently states, “Why should men be the only ones who are allowed to go off and have big adventures on their own? When I was a girl, the thought of me driving alone through Africa would have been utterly absurd—but the world has changed, and I’m jolly glad it has.”

Follow in the footsteps of these and other female adventurers on our Women’s Journeys.

Header Photo: American explorer Harriet Chalmers Adams (1875-1937) in the Gobi Desert. Inscribed: “To H.E. French, with greetings from the Gobi, by Harriet Chalmers Adams.” © Library of Congress, Public Domain